With decades of experience across electrical engineering, safety, and power infrastructure, Dianoush Emami brings a practitioner’s perspective to foundational physical principles that shape modern systems. Educated in electrical engineering at the University of Southern California, he began his career working on overhead and underground electrical systems supporting both nuclear and conventional power generation. That early exposure to large-scale energy projects informs a practical understanding of how theoretical concepts translate into real-world applications. Over a career spanning nuclear, fossil fuel, and alternative energy facilities, he has also contributed to high-voltage transmission design, substation grounding analysis, and project management. These experiences provide relevant context for examining the Faraday effect, a phenomenon that underpins optical isolation, sensing, and communication technologies used throughout the electrical power and telecommunications sectors.

The Faraday Effect: Linking Electricity and Magnetism

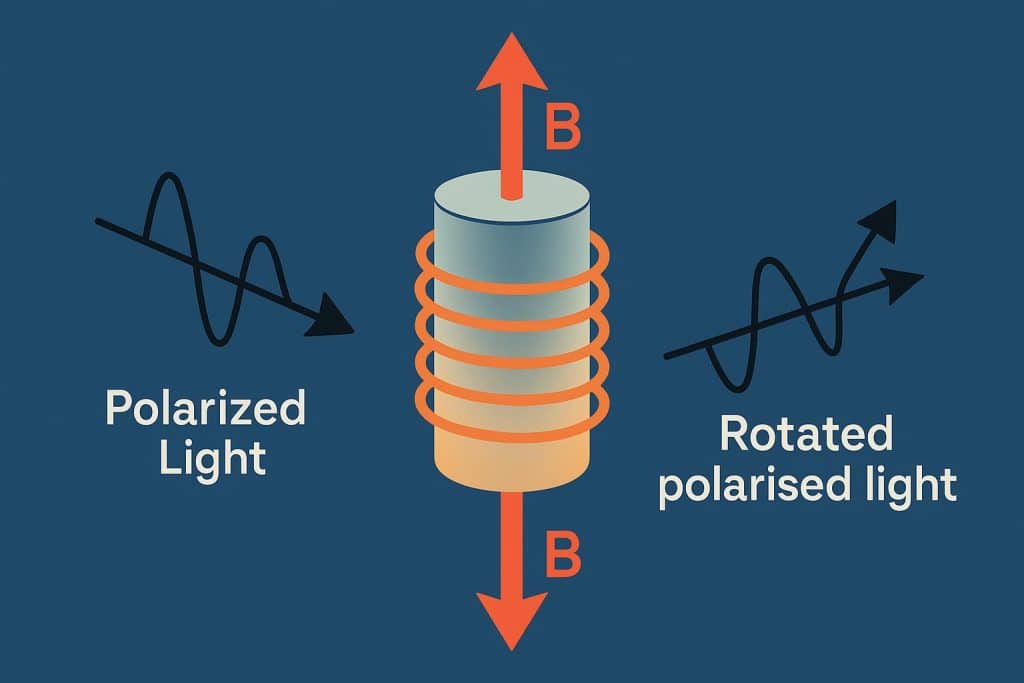

One of the key principles of electrical engineering and physics centers on the Faraday effect. Discovered by Michael Faraday in 1845, it describes a process of optical rotation, or the rotation of a light beam’s plane of polarization (or vibration) when placed within a uniform magnetic field. In demonstrating this effect, Faraday first created plane-polarized light waves.

Light waves normally vibrate in two planes, which are at right angles to one another. However, when light passes through certain substances, vibration in one plane is eliminated. Faraday took such a plane-polarized light wave and directed its light path parallel to an applied magnetic field. This resulted in a rotated plane of vibration, with the phenomenon working in many types of liquids, solids, and gases.

Faraday also found that the direction of rotation and direction of current flow in the electromagnet were the same. What this means in practical terms is that reflecting the same light beam back and forth through the medium increases the rotation of the light beam each time.

This discovery linked electricity and magnetism, which scientists long held to be separate forces, as interrelated phenomena. In 1905, Albert Einstein conclusively reiterated this connection through his special theory of relativity. Despite these connections, electrical and magnetic forces are distinct and require different equations. Electric forces are generated from electric charges that can be at rest or in motion. By contrast, magnetic forces are solely generated by moving charges and only act on charges that are in motion.

The Faraday effect has many practical applications, including Faraday rotators and isolators. These optical isolation devices prevent unwanted optical feedback and back reflections in media such as fiber optics, telecommunications systems, and lasers. They improve signal quality, safeguard the integrity of optical components, and regulate and stabilize laser performance.

As an example, engineers employ the Faraday effect in creating non-reciprocal devices that only allow light to travel in a single direction, with reverse travel blocked. This helps prevent signal interference and ensures that the data in optical communication networks is safeguarded and secure.

The Faraday effect is also applied to magnetic field sensors and magnetometers, as it measures polarized light’s rotation as it passes through a material within a magnetic field. This enables a precise calculation of magnetic field strength and is critical in areas such as materials testing, geophysics, and even navigation. Scientists may extract vital information about the electronic, optical, and magnetic properties of a material.

Within the quantum information processing sphere, the Faraday effect helps manipulate single photons and their polarization. This enables the placement of quantum gates and other components used within quantum computers and communication systems.

The effect even applies to magneto-optical imaging for therapeutic medical applications. Here, the rotation of polarized light is used in conjunction with biological tissues’ magnetic nanoparticles in visualizing and detecting the body’s magnetic phenomena.

One emerging (and to date, theoretical) use of the Faraday effect proposed by researchers involves using lasers to generate magnetic fields an order stronger than any occurring naturally on earth. Such super-strong fields are presently only found in space. Their potential uses include modeling astrophysical processes within a lab setting and harnessing nuclear fusion’s clean power.

About Dianoush Emami

Dianoush Emami is an electrical engineer with 37 years of professional experience in California. He holds a bachelor of science in electrical engineering from the University of Southern California and maintains Nuclear Regulatory Commission certification. His career includes work in nuclear, fossil fuel, and alternative energy facilities, as well as high-voltage transmission and substation grounding. He is an active participant in IEEE committees focused on distributed generation and switchgear safety.

Angela Spearman is a journalist at EzineMark who enjoys writing about the latest trending technology and business news.